Greater Elements / Lesser Mysteries

- christiansager

- Mar 13, 2020

- 6 min read

You probably already know that writers eavesdrop on your conversations. Look around. We’re listening right now. As I’m writing this in a bookstore cafe I can overhear the employees having a conversation about the new Sonic the Hedgehog movie. One of them is trying to convince the others to go see it, and like me, their colleagues are skeptical. Not because they think Sonic is inherently imperfect, but because their colleague cannot describe what makes the film worth their effort. Instead, she keeps framing it within the context of her own life and her long relationship with the video game character it’s based on. This is a common problem we have. We don’t know how to talk about the stories we’re constantly consuming. No slight against the bookstore employee I’m overhearing, because most of us lack the same terminology for storytelling. Even an employee at a store that sells books doesn’t have the ability to assess the stories within them.

Whether it’s a graphic or prose story we’re reading, a TV show or a movie we’re watching, or even the news or social media posts we read on our phones, stories are everywhere. Qualifying these stories is an important skill. It's also a larger part of the media literacy that we don't prioritize. We need a common language when we talk about stories and the ways we receive them. I get that most people want a certain amount of mystery to how their stories are made. Seeing all the gooey bits molded together into sausage isn’t appealing (see below). But we still put food labels with facts about nutrition on sausage packages, don’t we? We know what their ingredients are, even if there’s too much saturated fat or sodium. And, most importantly, the people making the sausage know what goes in it.

Years ago I heard an account of two popular comics writers meeting for the first time at a company dinner. Let’s call them Jason and Brian. Jason was new to the industry and had just published his first creator-owned graphic novel. Brian was a decade older, kind of a luminary. He asked Jason what his book was about. When Jason started telling Brian the events in his story, Brian cut him off, saying, “I didn’t ask you for the plot. I asked you what it’s about.” Despite being kind of a jerk about it, Brian had a point. At the same time, his terminology was too vague for Jason to understand. How could Jason know what he really meant was, “What are the themes in your comic?” Their conflict arose over a simple misunderstanding that could have easily been resolved if they were both using the same vernacular. One of the first things we need to define about stories is what they’re made from. And it ain't sausages. This is important not just in how we create our stories, but also in how we measure their success. Think about how many reviews you've read that use the terms “good” or “bad” to judge a story. That boils down to a reviewer’s opinion, usually based on how their personal experience responds to the narrative. Sure, that tells us their emotional reaction, but it’s not helpful if we’re looking for them to be gatekeepers who help us assess whether these stories are worth our time, money and attention. You might be thinking, “Surely this is something you learn when you study literature in school?” Definitely. But scholars don’t seem to agree on which model to use. Some approach stories through literary criticism, others through formalism. “New Criticism” used to be the dominant model for this. Learning literary elements is supposedly a common feature of education at both the primary and secondary level. That wasn’t my experience in school. Even if it were, we’re still not using the same terminology to discuss and understand the basics of storytelling.

So what’s the solution? Personally, I like the blueprint Jeff Vandermeer uses in Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction. It’s a book I find myself turning to over and over again in my own crafting of stories. While Vandermeer is a speculative writer, don’t let the title scare you away. You don’t have to be writing horror, fantasy or science fiction to learn something from his lessons. I think the anatomy he articulates works well for all storytelling, even non-fiction. Vandermeer uses biological metaphors through Wonderbook to dissect stories. Each of these exist within an ecosystem that he breaks down into the “Greater Elements” and “Lesser Mysteries” of storytelling. I’ll share them below. If I’d actually seen Sonic the Hedgehog, I suppose I could supply examples from it so we could stick with a single case. I considered using one of my own stories, but that seemed a little pretentious. So let’s use the 2019 film Parasite, since it’s critically acclaimed, widely available and the subject of much water cooler discussion right now. Especially since The Bad Penny publicly mocked it. Here's how you explain why it deserved the awards it won.

The seven “greater” elements by Vandermeer’s count are:

Characterization: How the people in the story seem real or interesting to us. Example: Each of the 8-10 main characters in Parasite stand on their own as believable individuals. This is because they each have clear wants, needs and fears, that provide us with emotional identification. The conflicts these characters produce also organically drive the plot forward.

Point-of-view: The perspective the main characters are seen through. Example: Even though it’s technically limited third-person perspective, Parasite’s story is told from the Kim family’s POV, with the son Kim Ki-woo as our protagonist.

Setting: The physical environment the story takes place in. Example: Parasite’s story is set in present day Seoul, Korea. But our main locations are within the homes of the Kim family’s basement apartment and the Park family’s expensive, multi-level house.

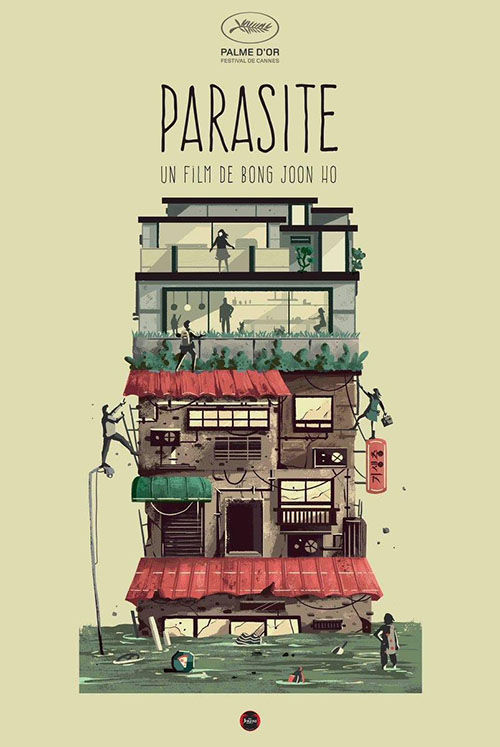

Art by Andrew Bannister

Plot: The sequence of events expressed through scenes. Example: In Parasite, the members of a poor family scheme to become employed by a wealthy family by pretending to be qualified individuals.

Dialogue: The conversations conveying what the characters communicate to each other. Example: Since I don’t speak Korean, it’s difficult to parse how Parasite’s dialogue captures the characters precisely. But even through translated subtitles you can tell that the words each character speaks demonstrate what their needs and conflicts are.

Description: The details of a scene. Example: Parasite is a film, so it uses visual presentation to render each scene's details. Think about the difference between the Park’s house and the Kim’s apartment. The art, set and costume departments had to render that reality for us, the same way a prose writer would through description. Also, notice the difference in how the lighting and color palette change between the two locations.

Style: The way words are arranged to tell the story. Example: Since Parasite is a film, it doesn’t have the ability to manipulate words to establish a style. But Bong Joon-ho makes use of the language specific to the medium of film to create what is referred to as a “black comedy thriller.”

Next come the “lesser” mysteries in Vandermeer’s ecosystem. This is where terminology gets a little more vague. If you prefer ambiguity in the sausages you eat, these terms are for you:

Voice: The writer’s worldview, peeking through the story. Example: From Parasite and Bong Joon-ho’s other work I get a sense that he’s a guy with a dark sense of humor who enjoys using the macabre to prove a point. He criticizes capitalism and other social structures through his stories, but doesn’t seem to be preaching. In fact, I get a sense that like Kurt Vonnegut, he’s more bemused than depressed by the human condition.

Structure: The arrangement of scenes in the story. How things happen, not what happens. Example: Until its conclusion, Parasite is arranged in a fairly linear manner. Toward the end however, the story shifts away from reality to a fantasy in Kim Ki-woo’s head.

Tone: The mood evoked by the story. Example: Parasite is called a “black comedy,” because it is simultaneously humorous and dreadful. You'll laugh, you'll cry. You'll never want to leave the house again.

Theme: What the story means beyond the events described to us. Example: Parasite shows that Bong Joon-ho is interested in issues of class. He uses the contrast of upstairs/downstairs lifestyles within a singular home to highlight social inequality. Parasite also seems to be about the toxic nature of capitalism and the inevitable repercussions climate change will have on us all, no matter how wealthy we are. Form: The format of media the story is rendered in. Example: Parasite’s story is told through film. It’s 132 minutes long. It was distributed first in theaters and then on home entertainment like DVDs and streaming services.

Being able to distinguish between these twelve terms makes a significant difference when we share information, about both our own and other people's stories. I feel my work is far richer ever since I started applying it to my own storytelling. What's especially helpful is that now I can articulate why it doesn't work and try to fix it. Now go eat your sausages.

Comentarios